NEW

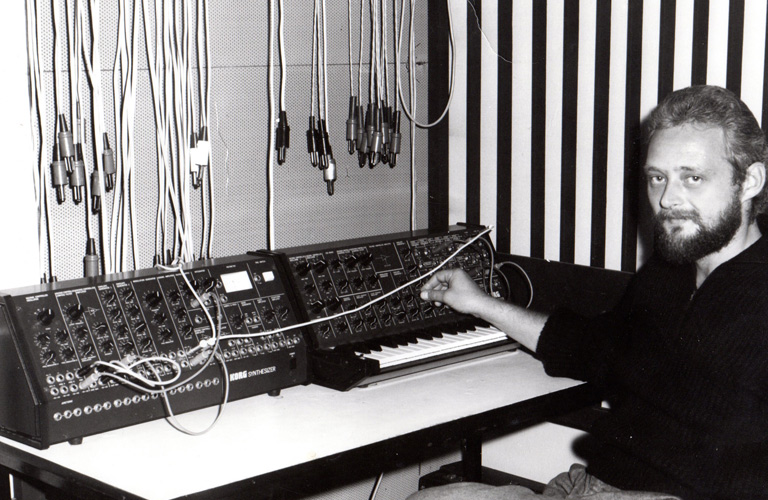

Artist Interview: Andreas Kaufmann

Just a short look at his website already reveals how diverse this man is: Speaker repair and construction, video editing, music production, audio conversion – it’s all part of “Soundjack” Kaufmann’s repertoire. But he doesn’t do it to pay the bills. He truly enjoys his work and his retirement to the max. In the course of the conversation it becomes increasingly clear that he has more than enough experience and know-how to take on many projects and speakers.

Between 1976 and 1986 you worked as a sound assistant at the German Democratic Republic State Film Studios (DEFA). Afterwards, starting in 1986 and until retirement, you worked as a sound engineer in film and for TV, for German series such “Polizeiruf 110” and “Wolffs Revier”. What are some of the most significant changes that you experienced in the course of your career as an audio engineer in film? Which have challenged you the most?

When I started back in 1976, 95% of films made at DEFA were completely dubbed, meaning that the sound recorded on the set was used solely for information, to know what the actors had to say during dubbing. This was due to the fact that the cameras used for filming weren’t soundproofed, and camera noise was constantly audible. Of course, even back then it was possible to place the camera inside a case, but this made it bulky and heavy, and most directors – especially cameramen – didn’t want this, because it meant a lot of extra effort and made the camera unwieldy. An additional point in favor of dubbing was that actors could afford to misspeak, and “it’ll be dubbed over anyway” was the standard excuse. Of course, even back then there were directors who knew that original audio would always sound more authentic. That made for a completely different atmosphere on the set. It had to be completely quiet when the camera rolled, there was no chit chat, no ambient sounds like construction noise: everything had to be shut down. But this definitely paid off because sound dubbed in the studio is always sterile. And on the subject of studios: One of the biggest changes that characterizes today’s shoots is that, at least for TV productions, almost no indoor scenes are shot on a studio set, but rather in original apartments, offices, etc., which also has its financial advantages. However, this environment places higher demands on those on the set. There’s little room and hardly anywhere where you’re not in the way or the frame. And, since we’re talking about sound, the effect of ambient noise is significantly higher here. A construction site springs up in front of the apartment overnight, the neighbors are watching TV, the heater suddenly starts making noise next to the camera, or the refrigerator is too loud. “Yes, you can unplug it, but don’t forget to put it back, or else it’ll be a mess here tomorrow.” Don’t laugh – this has all actually happened.

Digitization has made many things easier in postproduction, and has even made it possible for consumers to record video and audio in their own home. What skills that you’ve gained by working with analog recording devices and audio sources would you, nevertheless, not miss?

Listening! Digital recording technology is a blessing because it’s easier to operate and there are a lot more options. But if I can’t hear mistakes during recording, there’s no trick in the world that will make them disappear afterwards. Of course I can restore poor recordings up to a point, but it is always a compromise.

Do you approve of all the innovations that digitization has brought along with it or do you miss some things like a specific sound or the work process?

Certainly not the work process! As an example, many times I’ve had to record two music tracks in one setting for playback recordings! After the tape is made with the right sequence, the director comes and says: “I’ve thought about it (here’s where the alarm bells begin to ring), and I’d like to have the second track first, and the first should play as the second.” No problem, but it will take a while. So, rewind tape to the first song, cut, … oh, there’s no extra empty reel… what now? The tape with the first song unwound on the floor, the second song wound back on the reel, the piece from the floor attached (hopefully the right way) to the end of the first song (woe to him who has no reverse side adhesive at hand), wound back, done. Takes at least 10 to 15 minutes. Today, every song in Samplitude is an object in VIP and all of this doesn’t take even a second.

But sound is a different topic. When I want to listen to music, and I mean really listen, not just while I do something else at the same time, I play an LP that’s been created from start to finish using analog processes. Now this sounds great. Of course, it also depends what one uses to listen to the music. It’s wonderful that LPs are being produced again, but I think this is happening for purely financial reasons, since the chain of processing before pressing is still completely digital.

As a restorer of old GDR speakers and thanks to your long professional experience, your ears have had a thorough training. On your website you also offer digitization of video and music cassettes. What are some of the avoidable mistakes your customers commit when recording sound? What should you pay attention to when mixing?

This question cannot be answered in general. I can only give a tip concerning microphone recordings: The audio source must, and I deliberately say “must”, be as close to the microphone as possible, as it is the only way to minimize noise. And, please, never record with automatic modulation, this is never a good idea! For everything close to the microphone, the levels will be adjusted well, but what happens when, for example, no one is speaking for a moment? The automation will then raise the background noise, and no one wants that. This is what I have to combat most often when editing video, and not just with analog video recordings. Even today’s digital camcorders focus only on getting high image resolution, and leave sound quality by the wayside, even when the manufacturer praises his “zoomable” microphone. This function simply limits the microphone’s stereo base, magnifying the signal coming from straight ahead, but if I zoom in an image of a large head from 5 meters’ distance, the distance to the microphone remains 5 meters, and the microphone will record everything that happens in those 5 meters, period. And this brings us to the basic anatomic human quality: Our sight is oriented only to the front, while our hearing works all around us, in front, in the back, above, below. If I’m in the forest with my girlfriend, having an idyllic picnic, I might say “Look at the clearing, isn’t it lovely here!” But at home, watching the video, it’s not lovely at all. What I hear is: “Where’s all that noise coming from?” Wasn’t there a construction site at the edge of the forest? I didn’t even notice it at the time. And there’s the mistake! “Didn’t notice it.” Our brain is wired to ignore noises that we don’t want to hear, but the mike can’t do that. So now we’re back to the basic principle of audio recording: “Listening”.

Do you just rely on hearing when monitoring audio or evaluating restored speakers? Or do you use any other tools to help you assess audio quality?

Listening is the final check. First of all, you subject individual components to a range of tests. Switches are tested for frequency response and each speaker chassis for impedance response. If there are any deviations, I always try to assemble parts with equal measurements. But the most important thing is, and always has been, evaluation through listening. Listening is always subjective. So I prefer it when customer collect their speakers from me directly, so they can bring their favorite music along and then give me their personal impression of the sound. It’s something I can learn a lot from too, because like I say, listening is subjective.

What do you need to pay attention to when reducing original sound, so that recordings sound “realistic” (footsteps, voice far away or near, left/right etc.). Or is this step more part of postproduction (in which you’re no longer involved)?

“No longer” involved in postproduction is correct, because that’s been the case since the free market came into existence. In the GDR State Film Studios (DEFA) era, a sound engineer was responsible for sound right from the first take to the last day of mixing. That was a good thing, because things that were agreed upon during recording could be followed up then and there. When you’re no longer involved in the mixing process and then at the end are faced with the end product, you’re often told: “That wasn’t the take I did…” Then it’s the case of “Well, who recorded the sound?” And I’m not there to defend myself.

For original sound, the most important thing, or rather the only important thing, is what happens in the frame. And perspective is an important factor too. So close-ups have a closer sound, while long shots that can still be made out are given a total sound. This is the problem that sound engineers face today. It’s common practice to film the same setting with two or several cameras simultaneously, which results in different sizes in image. Any decent boom operator can work with a group of actors at a distance, but only insofar as the image border allows. If two cameras are used to create two recordings with differently sized images, the hand-operated microphone can be brought to the image border of the long shot, but the close-up requires a closer sound. So what do you do then? A hidden microphone that should not be visible on camera is attached to each actor in a scene. The sound engineer might have three, four, five or more microphones attached to the recording device. So you’ve everything ready to go. Hidden microphones can be annoying, though. Since they’re concealed underneath objects, the sound isn’t clean and is affected by frequency response. It’s hard to believe it, but items of clothing can be really loud when they rub against the mike. I hate silk neckties for this reason. So, coming back to the mix, it may be the case that someone asks “That sounds strange – who recorded the sound?”. If I were there at that point I’d say: “The person who thought it was a good idea to film with lots of simultaneous cameras!” One of my favorite sayings was: “A director gets the sound that they direct”, but the meaner version of this is: “A director gets the sound that they deserve”.

As well as audio restoration, you offer studio recording for vocals and instruments. How is your studio set up? What devices and software do you swear by? Do you only use RFT speakers in your studio too? What type of recordings take place in your studio?

There are so many options on offer that I wouldn’t describe it as a studio. It’s more of an all-purpose room where vocal recordings can be created even on a small budget. Parents come in with their kids at Christmastime to create Christmas CDs with songs for grandparents. And for these kinds of tasks I swear by Samplitude, because it lets me work on so many tracks to create a great track from a number of recordings. And when nothing else helps, I use Elastic Audio to fix the rest.

RFTs are all I need for listening back. As my main stereo speaker I use a BR50 in a casing I’ve constructed myself, two BR26 speakers set up the sound behind me and in the center I have a BR3010.

What’s been your most difficult restoration to date? And how did you resolve the issues with it?

What does difficult mean? You only ever make things difficult yourself. When you know your options for solving a problem, then you’ve already solved it. There are no problems, only solutions. There is no “It won’t work”. It might be the case of “Not this way”, but there is always a compromise that everyone can live and work with. Something I really remember was the life story of an 80-year old gentleman recorded onto a dictation device which had a built-in microphone, automatic recording controls and automatic disabling for periods of silence. The operating noise of the cassette was almost as loud as the man’s voice, at every pause the device switched off and then switched on again upon hesitations in speech so that the first syllable of a word was often cut off. The main work was carried out by the Cleaning & Restoration Suite. It’s a powerful tool, so there’s minimal effort required: just cut, copy & paste.

You’ve been a Samplitude user from day one and have been working with the software since it was distributed under the SEK’D label. Why have you always kept on working with Samplitude?

I love the virtual workflows. That’s what excited me about the program from the start. It was something that wasn’t really around in the beginning of digital audio editing – at least not in the affordable amateur and semi-professional software area. Samplitude was the first program to include it. And also, with each new version there are lots of new options, not just a redesigned interface.

How do you think Samplitude has changed over the years? Which new features have you particularly enjoyed?

Samplitude has in my opinion grown from a small semi-professional program to an-encompassing, professional program. In each new version I’ve discovered features that have expanded my options even further.

Which functions could you not do without?

Features that I consider irreplaceable are the Cleaning & Restoration Suite, as already mentioned, and also the option to burn directly from the VIP.

Our thanks to Andreas for this interview.

If you’d like to find out more about “Soundjack”, visit his website: http://www.tonkeule.de.

Or read another fascinating article about him at https://www.amazona.de/interview-andreas-kaufmann-tonkeule-de/.

Next Post >

Artist Interview: Cyril Picard

< Previous Post

Artist Interview: Jairo Bonilla

Related Posts

Interview with producer Garry King

In this interview, drummer and producer Garry King shares his tips and experience on recording drums the right way.

The new Samplitude Music Studio

Samplitude Music Studio – the entry level DAW that gives musicians everything they need. We'll show you all news.

Artist Interview: Jairo Bonilla

The Columbian producer Jairo Bonilla shares his valuable experiences and tips for using Music Maker to create advertising music with us.

Artist Interview: Siegfried Meier

The producer, engineer and founder of the legendary Beach Road Studio, Siegfried Meier, talked with us about his work.